A Conversation with Tilly Moses on Fashion as Agency, Disabled Artistry, and Creativity in Illness

Conversations Behind the veil 005

In the fifth edition of Conversations Behind the veil, I spoke with Tilly Moses—disabled writer, former folk musician, and creator of a wonderful self-titled Substack, where she shares reflections on illness, identity, and joy, alongside whimsical glimpses of second-hand fashion and craft.

We talk about navigating the shifting landscape of chronic illness, the power of self-expression through style, and the ways creativity finds new shapes when the old ones fall away. Tilly writes and lives with candor and warmth, offering an honest account of what it means to keep making a life within limitation.

This series is a space for honest, unguarded dialogue with fellow artists and writers. We explore the unseen: chronic illness, creativity, queerness, neurodivergence, and the quiet work of staying whole in a fractured world.

Content note: This conversation includes themes of grief, loss, and trauma, alongside creativity, identity, and care.

vōx: Tilly! Hello, hi, nice to meet you and thank you so much for joining me in conversation today.

I have to admit, my first introduction to you was through your incredible eye for color and fashion! As a fellow fashion-loving girly, I’ve been mesmerized by your style skills. For me, style wasn’t innate. People are usually shocked to hear that, but it took me many years to get to where I am now. I’m still discovering new ways to dress pretty much weekly whenever I scroll social media.

Where did your style come from, and what inspires you?

Tilly Moses: It does take a really long time to develop personal style, and it takes commitment and work! When people ask me how I dress the way I do, the best answer I can give them is that I spend so much time doing it, so I really know what you mean about not getting there overnight. I also think our style changes as we change, and that’s one of the fun things about it - we’re never the same person, so our self-expression through clothing should reflect that.

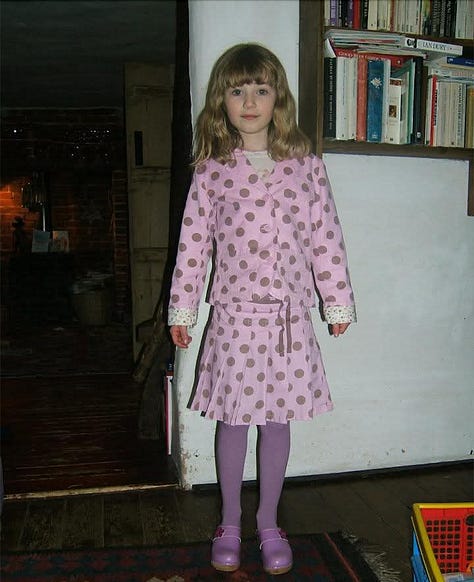

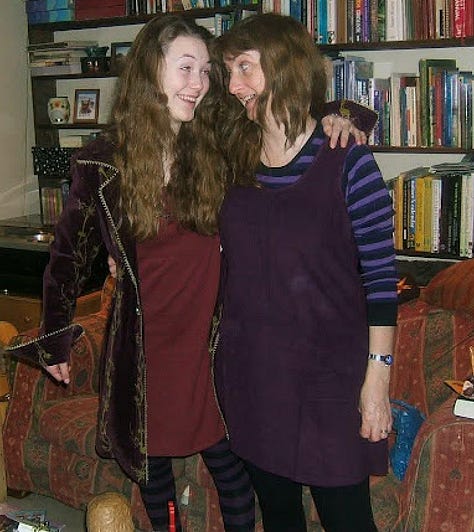

Ever since I was very little I’ve always loved clothing - I love how it gives an impression of the person wearing it, how it’s used to express identity as both an individual and as part of community groups, how it reflects so much history and human culture. When I was little I was drawn to the bright colours, textures, and endless fun you can have with it! My Mum is a really funky dresser, so I definitely get a lot of my style from her - she loves slightly whimsigoth 90s clothes, lots of velvets and corduroy and plum purples, very whimsical and gorgeous. She used to wear the (now very in vogue and beloved) El Naturalista swirl shoes to work most days, even when they weren’t part of the fashion zeitgeist at all at the time - I think her sticking so much to her own style over the years has been fantastic inspiration for me, because it never even occurred to me that I should be driven by what was in fashion. I grew up very rurally too so, to be honest, I had no idea what was in fashion outside of what I saw on adverts on TV. The confidence my Mum gave me to dress however I wanted, and the space away from other influences, meant I had a lot of time to develop my style during years I think a lot of others were maybe dressing to fit in. It’s a huge privilege to have had that time and it’s stood me in good stead!

A moment that stands out is actually a conversation with my Nanna - I remember her taking me to her wardrobe and teaching me how to colour co-ordinate. She took a dress out of her wardrobe, showed me how it had little spots of yellow on it, then she picked yellow tights and a yellow handbag, and blue shoes to match the base colour of the dress. It sounds basic, but I was probably only 6 or 7, and it gave me a little rule book for how to approach dressing. It’s still one I use every single day - it’s so simple, so straight forward, and allows you to curate an endless wardrobe that all mixes and matches with itself. People think of rules as curtailing creativity, but I find that this one really enables mine

In terms of what inspires me outside of these early influences, I definitely take cues from nature and often find myself mirroring what nature does throughout the seasons - in autumn, I favour rusty colours, deep purples, warm greens. In summer, I find myself drawn to lighter pieces with brighter colours. I even have items of clothing I bought or made specifically because they reminded me of nature - my moss cardigan, for example, that looks like it’s growing on you when you wear it. Other inspirations include other people I see out and about, who style themselves in their own ways, and give me new ideas for ways to approach dressing. Also, TV and film plays a big part in my styling - I’ll often see a character rocking something I’d never have considered wearing, and it opens up a whole new avenue for me! I have whole pinterest boards with particular fictional characters’ outfits pinned for reference.

vōx: Oh my gosh, I love this! It’s beautiful how you’ve carried on a lineage of stylish, creative women in your family.

I really loved your piece touching on disabled joy and how you express it through what you wear as an act of revolution. When did you first realize you could flip the script on folks who might look down on your disability–turning their gaze instead into curiosity or even envy at your confidence and joy?

I also deeply relate to what you write about navigating the medical system as a woman. As an autistic woman who masks heavily, I constantly consider how I’ll be perceived. I often wonder whether I should look put together to gain respect and avoid infantilization, or whether I need to perform my symptoms, putting on a kind of “pain show,” to make sure my suffering isn’t dismissed.

I’d love to talk about how you navigate this balance, if you’re willing to share.

Tilly: I think it was a gradual process, because I've always dressed unusually and loudly, and have always been stared at or approached for it (in both positive and negative ways). So I just kept doing that as I became disabled. But when I started to use mobility aids (which in my case was not synonymous with me becoming disabled as, in hindsight, I’d already been disabled for many years), I realised how hostile people are to disabled people in public. It was truly like walking through a curtain and seeing what was behind there and, once you know, you can't un-know it. People are vile to visibly disabled people - there is a suspicion and a vitriol unlike anything I've ever experienced before. Perhaps the only comparison in terms of the traumatic level of vitriol is when I was a young woman speaking out honestly about how my male peers were treating me - the institutional gaslighting and silencing was extraordinary. But when that happened, there was an instigating incident - I put my head above the parapet and faced the consequences. For disabled people, the instigating incident is simply existing in public.

I realised quickly that I had to have a set of defences to deal with this, and as joyful dressing was already part of my MO, I thought I should lean into that. I kitted out my first walking stick with colourful washi tape and named it Wilbur, and quickly started getting compliments on the colourful nature of it. So I decided to branch out and get walking sticks that I could match to my outfits - this effectively diverted people from asking me inappropriate questions about my body to complimenting my stick, about 60% of the time. When I got my wheelchair, it was so drab and black and boring, so I got to work personalising it. My favourite thing about going out in my chair is children's enthusiasm and fascination when they see it - they're drawn in by the colours and stickers, and I get to talk to them about it and call it my “freedom machine” and give them a beautiful, positive early interaction with mobility aids and disabled people. It's so gorgeous. As these interactions started happening more, I was reading a lot of political theory and books about disability ethics, and I learned about the medical model and the Social Model and about the concept of Disability Pride. This helped me to understand the importance of these interactions, and put them into a political framework, so I could understand the political inferences of re-routing would-be intrusive conversations about my body into interactions about colour and joy.

Now, this approach isn't a fix-all - I still can't access loads of public spaces, people still shout slurs or ask me inappropriate questions, and I absolutely do not have equity in my community. But it gives me a sense of autonomy, of reclamation over my body, and a feeling of confidence. Over the years I've only become more flamboyant, which I think would have happened anyway to be honest, but being disabled makes the context of this different, and I'm glad to have this tool set to deal with some of the trials of being disabled in public. No-one should have to have it though - we should be able to exist without armour. That's what needs to change.

Interacting with the medical system as a woman, especially a neurodivergent and/or disabled woman, is a nightmare. From a very young age, I was having less than stellar experiences with medical professionals - special shout out to the doctor who, after years of me trying to get a diagnosis for whatever it was that was making me pass out at random intervals, did the “cuckoo” hand gesture to my mum in an appointment to signal that I was “just crazy.” I learned fast that how I looked mattered, but it seemed that every doctor had a different preference, so if you were going to a new one, you had to try and hedge your bets. Some doctors think, if you're dressed too intentionally and with a full face of makeup, then you're absolutely fine. Some, because of their raging misogyny, won't take you seriously based on their subconscious distrust of anyone who looks “too feminine.” Some, if you're not dressed well, won't take you seriously based on the idea that you don't take yourself seriously, or that you don't “take care” of yourself (as if caring about yourself is straightforwardly reflected in your appearance). It doesn't stop there either - add in fatphobia and that triples the complexities to navigate. I can't speak on it because I'm white, but I know black women and women of colour have another set of complexities to work through here too.

Your presentation of pain matters too. Once, when a joint in my lower back had subluxed (partially dislocated), I got stuck flat on my back on my bed in excruciating pain. Josh and I had only just started dating. I was 19 and terrified. I called him in desperation - he arrived and promptly called an ambulance (over my weak protestations). The paramedics arrived, and started to talk to me about the situation, asking me about my pain levels. I answered that I was at about an 8/10 pain level, and the paramedic scoffed and said:

“You don't look like you're in that much pain at all, you look like you're barely in any.”

Used to this kind of nonsense, I rolled my eyes at Josh, and he had to advocate for me. Eventually, he managed to negotiate one small packet of codeine and muscle relaxers from the paramedic while I laid on my back and stared at the ceiling, concentrating on not crying. Once the paramedic left, Josh said “What did he want you to do? Just scream at the top of your lungs for 5 hours? We'd told him that's how long you’d been stuck in this position!” Coincidentally, a few days later my male housemate came home with triple the dose of codeine I'd been given for, in his own words, some “mild stomach pain.” Medical misogyny is wild.

About a year after this incident, I passed out getting off a train in London. I was on my own, half way through a 6 hour journey, with another change to make onto a new train. I was carrying a hiking rucksack full of my essential possessions, my mandolin (I'd been gigging), and my walking stick. At this point I couldn't afford to buy my powerchair so, even though it was incredibly unsafe, I was forced to rely on my walking sticks 100% of the time. A kind man saw me start to go down as I lost consciousness getting off the train, and caught me before I cracked my head open or was trampled by people, and he took me to the ambulance service at the station. I felt so, so sick. I can't adequately describe how unwell I felt- there aren’t words. The pain level, the fatigue, the nausea, the dizziness. I felt like I was dying. I tried to stay calm as they checked me out, but when they pronounced “nothing was wrong” and said I should just try and catch the next train, I started to cry. I was all on my own, in a huge overwhelming London station, feeling so ill I could hardly stay conscious, being told to figure out new train tickets and a new connection and making my way to platforms, and sitting on another train for hours before I could rest. It was too much, and I started to weep and say “No, I can't do that.” The paramedic looked at me and said:

“You're quite hysterical. Is this level of hysteria normal for you?”

I have never felt more heartbroken.

So you can see the catch twenty-two - don't express the pain and the pain isn't real to them. Express the pain and you're hysterical, and somehow the pain still isn't real to them. Be too put together and you're too well looking or too feminine to be taken seriously, but if you’re not put together enough it's your fault you're ill because you clearly don't care about yourself. Are you thin? You need to eat more - that's why you're sick. Are you fat? Everyone knows fatness causes every single illness in the world and you're lazy and morally reprehensible for allowing yourself to get that way, so that's why you're sick. The only way through that I've found is to try and learn what it is that specific, individual doctors like, then request appointments with them, and play along. But it is so exhausting. And it makes me feel such indignity. These days, I don’t really interact with the medical profession at all unless I can help it - I manage my conditions myself, and only go to the doctor when I have an infection or something that needs immediate treatment.

vōx: I truly have tears in my eyes from your recollections of living as a disabled woman. Many of these stories hit close to home. They’re heartbreaking. They also helped me put some of my own experiences into a new context.

I’m thinking about this time I was in London, February 2020 (oh, what an era!). I wasn’t yet diagnosed autistic, and my health problems had been brushed off so thoroughly that I either ignored them or assumed they were totally normal.

I was hitting all the fashion weeks that spring, so I had just been in New York and attended packed events all week. By the time I reached the airport, I knew I was getting sick.

The night I arrived in the UK was a horror show. I was staying with a friend and their three roommates, sleeping on a pad in the basement. After eating soup, I went straight to bed. Early in the morning I woke up feverish, tried to drink water, and ended up throwing up for hours, unable to leave the bathroom floor.

My partner

was in LA and even considered flying out. That’s how bad it was. Of course, we couldn’t afford that, so he urged me to get a hotel room. Not only so I wouldn’t risk infecting the roommates, but also because I couldn’t exactly commandeer their one bathroom while constantly throwing up.At the hotel, I kept getting worse. I couldn’t hold down even a drop of water and grew more feverish by the day. This had happened to me before with flu-like illnesses: I’d reach a point where I needed IV fluids or at least anti-nausea medication to recover.

After three days, I took myself to a walk-in clinic, where I sat in agony for hours before being seen. When I was finally called in, I was told it seemed viral and sent home, despite telling them I hadn’t kept down water for days.

Looking back, I can’t help but wonder if my autistic masking and female presentation were factors in why they dismissed me. I’m certain I looked less sick than I was. Masking is second nature to me, a lifetime practice.

Tilly: I wish I was surprised at this story, but I’m not at all! I’m so sorry it happened to you. You deserved better, and still do - we all do!

vōx: We truly do! I thought your recent post on how folks can be an ally to disabled people was such a fantastic overview. I especially loved your point that non-disabled folks should start pressuring spaces to have more accessibility and to list these things on their socials and websites.

As a disabled musician, I’ve often considered quitting entirely. I can’t keep up with my peers. I’ve had to change the way I play shows, create visuals, and work in studios. Nothing looks the same as it once did.

I wish people understood the sheer amount of stress and admin labor, as you put it, that goes into something as simple as attending an event, shopping, or eating out. I’ve had so many frustrating experiences trying to see live shows. Venue workers that scoff when you ask if they’d have a chair you could borrow. Spaces that are totally inaccessible where I’ve had to just turn around and go home.

The music industry is deeply ableist. Even the way artists are expected to tour, a show almost every night of the week for months in a row. It could burn out the healthiest, most able-bodied of musicians. And it does!

I’m currently working on a tour for next year, and accessibility is at the forefront. I won’t be able to perform more than 3-4 shows per month, unlike my old pace of playing that many in a week. Each show will come with a detailed audience guide covering COVID safety, mobility access, the exact timing of events, sensory expectations, and more.

When was the point in your life when you knew you had to leave the music industry behind?

Tilly: I love the sound of your tour and the guides you’re going to provide with all the access information - it’s a shame you have to take it into your own hands but your audiences are so lucky to have you doing that for them!

I’ve never really talked publicly about leaving music behind, but I think it’s been long enough now that I can start to. It is still painful - I spent a decade doing it and, for most of that time, I was gigging once or twice a week. I released two albums, I did two UK tours, I supported and collaborated with many of the great and good from the folk world. I made lots of friends through music (lots of whom I’m still in touch with, thankfully) and I’m grateful for everything it gave me. But, ultimately, I left the scene because of misogyny and ableism. And I still find that reality really painful to live with.

I started playing music in public when I was 13, which is very young. I was a confident and precocious teenager, with a certain wisdom beyond my years, but looking back now I definitely also had all of the naiveties of a child (because I was one). I’m not going to go into details, but I was on the receiving end of some pretty bizarre behaviour over the years, especially from adult men. At the time, I just kept pushing forwards because I loved my work and I believed, if I kept working hard enough, it would work out for me. But, as I got older, I increasingly recognised the bad behaviour and misogyny for what it was, and found it more difficult to roll with those punches. I was badly let down during the making of my second album and I started to feel disillusioned with it all. Brexit had made it harder to tour internationally, and when I toured the UK with my second album in late 2019, I realised I wasn’t enjoying it anymore - not in the way I had done. I suddenly felt strange opening myself up in the way I was doing - putting my most intimate feelings and thoughts into songs and then performing them to strangers suddenly felt wrong somehow. It was like my brain had just registered how objectifying it could feel, and how dangerous it could actually be to let strangers into my life in that way sometimes.

Then, of course, there was the inaccessibility - by 2019, my health had deteriorated rapidly, and I couldn’t gig in the way I used to be able to. That tour was only 2 weeks long, and it took me 3 months to fully recover. Folk venues, due to usually being smaller and more intimate, and often in old buildings, tend to be really inaccessible. Steps up to the green room, steps up to the stage, nowhere to lie down, nowhere I could take myself off and rest if I really needed to. On the last night of that tour, I lay down on a hard wooden floor and had a sleep before the audience arrived. I had to sit down for the set. When I got home, I realised how much money I’d lost, how sick I was, and how little I’d enjoyed it. I decided I’d stop - I’d done it for ten years, I was proud of my work and what I’d made, and I was ready to do something else. I was also ready to process my feelings away from an audience, in private - I just wanted to feel my joys and pain in all their nuance, without presenting it to others and having them applaud me for it. Two months after I made this decision, COVID hit. I couldn’t have kept being a musician if I’d wanted to. But I am incredibly grateful to have made the decision on my own, before it was stripped from me by force - so many musicians lost their livelihoods to COVID, and it was traumatic and awful for them. At least I stepped away before that. And, although my reasons to leave it behind were sad, ultimately I also just felt I wanted to try different means of creativity and that’s what led me here: to substack and clothing and writing. So it all worked out in the end!

The strange thing is, I’ve not picked up an instrument at all since March 2020 - I quit cold turkey. It was just really time for me. I think people find that strange, that you could spend so long doing something every day, and then just stop abruptly and never do it again (although never say never). But sometimes I think things just run their course and you’ve got what you need from them and then you don’t need them anymore. I am so grateful to have found out young that it’s ok to try something, to love it, and then to change your mind. It’s ok to fail! There is so much life and passion on the other side of failing and quitting. Do what you love until you don’t love it anymore, and then find something new to love - the world is big, you’ll find something else brilliant to do. Lots of people don’t learn this until quite late in life, so I’m really lucky to have learned it early. Also, none of those ten years were a waste - I learned so much about life, about people, about working in an industry, about patience, practice, commitment, travel, culture, and what it means to feel alive! I have carried all these things with me since. It’s never a waste to do something like that and quitting doesn’t take any of it from you.

vōx: I feel like I can relate to your timeline in many ways. I also had too many suspect experiences with men when I first moved to LA at 21 to pursue music. And it was during COVID when I lost all my income that my health also took a plummet.

I still don’t really know why that is. Maybe stopping everything gave me no choice but to face what my body had been screaming at me for years. Maybe it was that mysterious illness in 2020 that triggered my POTS, something many people now know can happen with Long Covid, but also with other viral illnesses. Whatever it was, I never recovered, in health or in music income, post-COVID.

Your insight feels so wise: to look at something you once loved, recognize it was harming you instead of healing you, and have the strength to let it go. That’s true self-care, choosing your needs over any job or title.

Tilly: When I got to university, I was removed from a lot of the stressors that had been causing me to be very unwell in multiple ways. But, rather than getting better, I immediately got much, much worse! So I think it’s a common experience that when you stop and have some space, you suddenly feel the intensity of how unwell you are, and often your baseline moves a lot lower than it was. It’s definitely also possible that the illness you had made things a lot worse - my chronic illnesses were triggered by having a very intense illness that almost killed me when I was 11. Long-COVID is nothing new really - those of us with post-viral chronic illnesses knew long before COVID what could happen. I’m sorry you’ve had such parallel experiences in terms of misogyny and the impact of COVID on your health and livelihood! But it is comforting sometimes to commiserate together.

vōx: I’ve also experienced this phenomena a lot, the baseline moving lower. It happened to me intensely after being diagnosed autistic too.

I’d love to know, if you could ask venues for a few specific accommodations, what would they be?

Tilly: In terms of things I’d ask venues to accommodate for, I’d say:

Make gigs safe for COVID cautious people - it is possible to run safer gigs and it is better for the music industry and for musicians to do this! Have a mandatory testing policy and a mandatory masking policy. This is so easy to enforce, not expensive to do, and it keeps people safe. Venues could also invest in a couple of small air purifiers that filter COVID particles out of the air - these are one time investments that you can then stick on in the room to minimise spread of COVID. They’re not expensive at all in the grand scheme of things. Venues could also just open windows and doors more! There are so many straight-forward precautions they could be putting in place to keep everyone safe.

Musicians catch COVID a lot, because they travel a lot and spend so much time in rooms packed with people. This makes musicians especially susceptible to disability via COVID, and many of them will then have to stop making music because they are too unwell to tour, and because venues are inaccessible to sick and disabled people. If the music industry wants musicians, it needs to prioritise protecting their health! And audiences should be protected too! It’s a win win situation for everyone, not just disabled people, but it would open music back up to many vulnerable disabled people too. Sadly, I rarely go to gigs at all anymore, because of COVID risk - I don’t miss performing but I do miss live music. I would give anything for it to be safe for me to go to gigs regularly again.

Disabled viewing areas that aren’t rubbish! I have had many experiences with “accessible viewing areas” where I can’t actually see anything and the staff have been hostile. If your viewing area is just a random bit of floor, not raised, to the side of the stage where standing people can impede the view, cordoned off with a rope… you do not have an accessible viewing area.

Ramps up to stages - disabled people make music and art too! We don’t just consume it!

Step free green rooms - by the same token as above, disabled artists should have access to the same green room spaces as other artists. I know of far too many disabled artists who have had to do their vocal warm ups and get changed in the bathrooms before going on stage, because they couldn’t get into the green room.

Disabled toilets.

Do not require proof of disability for disabled people to have their access needs met at the venue. This is another example of a catch twenty two that disabled people get caught up in - as we discussed above, medical professionals spend years gaslighting and ignoring disabled and chronically ill people. So it’s notoriously difficult to get a diagnosis. Many venues require proof of diagnosis before allowing access to their accessible spaces, which locks exhausted sick people out from resources they desperately need. Even once you have a diagnosis, some venues require proof of receiving benefits! Benefits are even more notoriously difficult to get than a diagnosis, and many people are so traumatised by the system that they don’t even apply anymore, as they’re so exhausted. And people hate that disabled people get benefits. So, we either traumatise ourselves getting them only to be despised on a grand scale, or we can’t have access to the accommodations we need in public. Ridiculous! I also, on principle, don’t want to share my private medical information and benefits history with random venues around the country - I have a right to privacy! The actual problem is that the resources for disabled people are always so thin on the ground that we’re made to fight amongst ourselves for them, being forced to prove that we’re more “worthy” than other disabled people in our communities. The solution is just to have more resources for disabled people - bigger accessible seating areas, more disabled loos. But that would cost money, so no-one wants to do that.

Think about seating carefully and have multiple seating options - chairs for those who need them, space for those in wheelchairs, etc.

Have a website that allows people to book accessible options without having to phone or email the venue - the time it takes to have to call and email every single venue I attend in public to ensure my access needs can be met is astronomical. So many venues now allow you to pre-buy a drink before the gig, but still don’t have any access booking options.

vōx: This list is fantastic. I especially love your point about letting people book accessibility options online! I hadn’t thought of that, but it would ease so much of the worry that comes with simply leaving the house.

Tilly, it’s been such a joy to chat with you today. I appreciate you opening up deeply about the power of letting go, your experiences in the medical system, and the ways you’ve used your amazing fashion sense to give you strength.

I’d love to know what things have been bringing you the most joy lately?

Is there anything else you’d like to add as we wrap up?

Tilly: Bringing it back to joy is lovely - I feel like I’ve focussed a lot on frustrations and trauma and discrimination in this interview, and what I’m always trying to get across is that disabled lives do not need to be more traumatic or sad than anyone else’s lives. They are made that way by ableism. All people have sad and difficult things in their lives, and disabled people will be no different. We’re also no different in having so many potential sources of joy and beauty and satisfaction, if we’re allowed by society to access them. Here are some of my recent joys:

Autumn is on its way, which brings with it so many fashion opportunities (hello layers), it waves goodbye to the heat-induced fatigue I’ve been suffering with all summer, and it welcomes in lots of beautiful foods to forage and harvest.

On that note, Josh and I foraged blackberries recently and then made earl grey cake with cardamom creme fraiche topped with blackberries. Then we ate it for breakfast every day for a week - what’s more joyful than that?

I’m planning my hen party (or bachelorette for the Americans) and I’m so excited to have a weekend away with my closest friends, being a bit silly!

I started embroidering my wedding dress properly this week and it’s so exciting to get going! It’s going to be a mammoth task but I am determined!

Josh (fiance) and Greg (cat) are constant sources of joy - my funny little family of gorgeous boys. Josh is an expert at unconditional love. Greg is an expert at chewing shoes. We all have different strengths to bring to the table.

It’s been so lovely chatting to you - properly cathartic! Sometimes it’s good to clear the pipes. I love your work, so it was a real honour to be invited to do this with you. Thanks so much!

Read previous conversations:

A Conversation with Madelleine Müller on Making Music from Bed, Grief as Practice, and Reclaiming Enoughness

In the fourth edition of Conversations Behind the veil, I spoke with Madelleine Müller—disabled musician, writer, and creator of The Bed Perspective, a Substack that traces the contours of life, art,…

A Conversation with Autistic Ang on Recognition, Unmasking, and Returning to the Body

In the third edition of Conversations Behind the veil, I sat down with Autistic Ang—writer, podcaster, and creator of Adulthood…with a chance of autism, a Substack that blends vulnerability and razor…

Reading this conversation nearly made me cry because of how terrifying it is to be unwell, ask for help and be scoffed at or gaslit. This has been my experience with the medical industry also. Autism makes it hard for me to advocate for myself as in the moment, I fail to recognise I'm being mistreated and even if I did recognise it words fail me in times of stress.

Tilly is so full of joy and this was a really insightful interview, thank you for sharing. Her positive outlook is one I hope to achieve.

Wonderful, eye-opening, in-depth interview. Thank you for sharing.